As central banks sound the alarm over an AI bubble, parallels with previous market manias cannot be ignored

Jeremy Warner

The Telegraph

It’s October 2027, and the poly-crisis that financial markets have long feared is unfolding at speed. Vladimir Putin has made strong gains in his war against Ukraine and has begun massing troops at Europe’s borders in readiness for invasion of one or more of the Baltic states.

In the Far East, China’s Xi Jinping is openly preparing for his long-promised assault on Taiwan, emboldened both by Putin’s success and Donald Trump’s drubbing in the congressional midterms, which have significantly reduced the US’s scope for effective retaliation.

In the Middle East, the fragile peace secured by Trump in 2025 has already fallen apart, plunging the region into renewed conflict.

And on the stock markets, it’s mayhem. Trillions of dollars of losses are being inflicted on the one-time boom sector of artificial intelligence (AI). With the global economy on the brink of recession and unemployment climbing sharply, it is clear that the market for AI’s services has been grossly overestimated.

Despite promises made by AI evangelists, productivity is flatlining. Far from improving output, reports suggest that AI is damaging many businesses where it has been most fervently applied. Some claims on which AI has been sold to investors and lenders even turn out to be overtly fraudulent.

Many of the mega-deals that characterised the latter stages of the great AI gold rush, with customers and suppliers incestuously taking cross holdings in one another, are fast unravelling in an orgy of litigation, broken promises and shattered expectations.

But that is not all. Overlaying the stock market crash is a debt crisis of monstrous proportions. Almost everywhere, bond market investors are on strike and interest rates are rocketing. Global governments are struggling both to refinance mountainous debts and to fund ballooning expenditures.

Private credit, a form of finance that has flourished outside the conventional, more tightly regulated banking system, is in meltdown, with the folly of lending to higher-risk enterprises unable to access credit elsewhere now cruelly exposed for all to see. Again, the losses are monumental.

So bad is the shock that the whole construct of competing fiat currencies, on which the world’s financial architecture is built, seems to be crumbling. Instead, states are hurriedly erecting financial border controls in a futile attempt to stop those investors who haven’t lost everything fleeing for safer shores.

But those investors are realising a dreadful truth: even if you can get your money out, there appears to be no safe place left to put it.

1929 redux

This is of course a wholly imagined, doomsday future. Yet finance is built entirely on trust and confidence and rarely has it looked quite so fragile as it does today.

Even the usually sleepy Bank of England and International Monetary Fund have now taken to warning about the possibility of a sharp, destabilising correction in equity markets, all puffed up as they are by fevered speculation over the potentially transformative powers of AI.

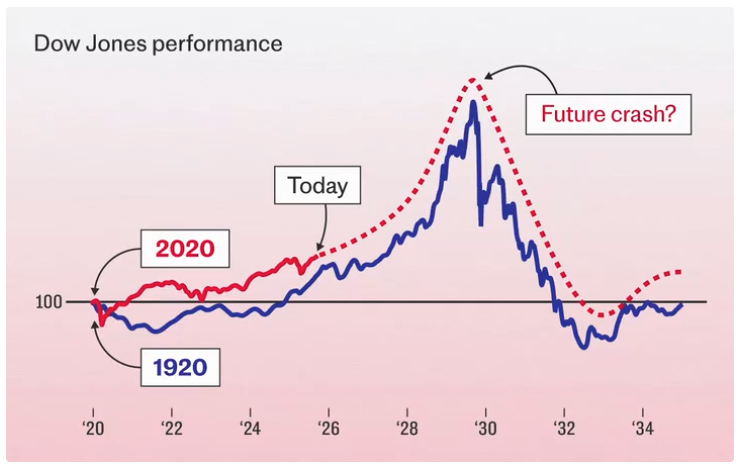

Valuations are stretched to breaking point, with the so-called “Shiller Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings Ratio” – generally regarded as the most reliable indicator of where the market is relative to past peaks – close to the all-time high it recorded during the dot.com bubble and slightly higher than it was before the great crash of 1929.

The parallels with previous market manias are striking.

Is this 1929 all over again? Surely not. We are all far too clever, worldly-wise and conditioned by the disastrous consequences of this most famous of stock market crashes to let it happen again. It’s unthinkable. Or is it?

When a banking titan as seasoned as Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JP Morgan Chase, openly expresses his concern, it’s time to sit up and take notice. Dimon said in an interview last week that he was far more worried than others about the possibility of a serious market correction.

There were a “lot of things out there” creating an atmosphere of uncertainty, he went on, citing geopolitical instability, unaffordable state spending and remilitarisation.

AI hype

Yet if it is not clear which needle will burst the bubble, there is no doubt about the bubble itself. The AI hype is off the scale, with the big prize dominance not of the generative AI chatbots that we have already become accustomed to using in our everyday lives, but of so-called “general artificial intelligence” or computers with cognitive powers similar to a human being, only infinitely faster and more powerful.

The dangers of AI fever are not just in unhinged stock-market speculation. Such is the magnitude of investment in AI data centres, connectivity and supercomputing that it is said to have contributed nearly a half of all GDP growth in the US so far this year.

The economy is becoming almost wholly dependent on just a handful of tech titan “hyperscalers” chasing a dream of uncertain substance and return. Rarely, if ever, have the fortunes of the world economy depended so precariously on the judgment of such a small cluster of men – the bosses of Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft, Apple, X, Amazon and others chasing the supposed crock of gold at the end of the AI rainbow.

Tech giants say this time is different, that unlike the dot.com bubble – which was characterised by lots of aspiring wing-and-a-prayer enterprises of hardly any substance – the current investment boom is substantially led by a small number of well-established, cash-rich mega companies easily capable of absorbing the new industry’s heavy upfront costs.

What’s more, they claim, AI promises an economic miracle that will render current concerns about spiralling deficits and fiscal black holes almost wholly irrelevant, with stellar growth fast eroding national debt piles.

It’s true that all booms are different, with specific characteristics and transmission mechanisms. But the one constant is that they always end in a bust. People forget that the dot.com boom was not just about transitory fireflies. It also included heavy investment in enabling infrastructure which came close to completely bankrupting many of the established and seemingly solvent telecoms players that provided it.

Such is the scale of today’s investment outlay, and the fear of being left behind, that even the giants of tech are increasingly having to dip into credit markets to stay in the game. Existing cash flows don’t cover it.

So intense is the competition for first-mover advantage that it is almost bound to end up with over-investment, and a world awash with spare data capacity looking for a use.

Hubble bubble

This is what the likes of Amazon’s Jeff Bezos mean when they talk about a “good bubble”. Some may lose their shirts, but the end result is a fabulous infrastructure that serves society at large and eventually “ushers in an era of abundance” for all.

What’s more, Bezos claims, when the bubble pops, it will sort the wheat from the chaff, so that only the strongest survive. No doubt he counts himself among the likely survivors. This is what happened with all previous industrial and technological revolutions, Bezos suggests, and the same Darwinian process will occur with AI.

Up to a point, he is right. In the early stages of the auto industry, there were more than 2,000 car companies in the US. Only a handful of them survived the subsequent consolidation, but it spawned an era of mass motoring that our ancestors could scarcely have dreamt of.

But the Amazon boss’s panglossian way of looking at the world glosses over the carnage this involves and the reality of what happens when the losses from too much investment crystallise. There follows an almighty credit squeeze as finance attempts to recover its footing, and a subsequent investment drought that sends unemployment soaring and wider economic demand plummeting.

There is no such thing as a controlled and gradual climbdown from excess. The transition from one economic age to another is almost invariably a financially, politically and socially destabilising catastrophe.

What makes the current bubble look doubly worrying is that it coincides, as rapid technological change often does, with a growing number of other potential crisis points. If it were just one vulnerability, then the world economy might be able to cope with any consequent mishaps.

But today’s political leaders are besieged by challenges and their scope for evasive action has rarely looked more limited. It is this confluence of negatives that perhaps provides the biggest cause for concern.

The multi-crisis

When the global financial crisis erupted in 2008, it at least found the world in otherwise relatively stable condition, with ample stores of fiscal and monetary firepower to counter some of its worst effects.

It was far and away the worst financial crisis since the 1929 crash, which itself resulted in the Great Depression, plus a degree of political and international instability that ultimately culminated in the Second World War.

Economic policymakers were determined to avoid repeating the mistakes made back then and collectively threw the kitchen sink at the problem, with unprecedented fiscal and monetary countermeasures backed by an equally unprecedented degree of international co-operation.

Remember Gordon Brown’s “I saved the world” gaffe when convening a meeting of global leaders in London to fight the gathering crisis? Well he sort of did by galvanising a global response.

It is hard to imagine such co-operation today. When the next crisis rolls in, it will encounter a world divided by competing ideologies and interests as rarely before, and certainly one incapable of putting up a united front.

Like the 1930s, it is a world defined by mountainous debts, remilitarisation, political instability and rising social discontent. Even if the international resolve was there to act, it is no longer clear that the resources any longer exist for the sort of collective bailout that might be required.

Both the fiscal and monetary canon were exhausted fighting the last crisis. There is no ammunition left. With the national debt swollen to more than 100 per cent of GDP in all bar one of the world’s major advanced economies, there is little if any fiscal scope for dealing with another financial market meltdown by borrowing from elsewhere.

The same may also be true of monetary policy, where central banks would struggle to repeat the rampant money printing of the post financial crisis era. Today, the adverse consequences of quantitative easing in stoking asset price bubbles and rising wealth inequality is becoming far too apparent.

It is not an experiment that policymakers would want to repeat.

Doubting the dollar

As it is, many economies are already close to breaking point. The canary in the coal shaft is the price of gold, which has soared in recent months and is signalling a growing loss of trust not just in dollar assets, but in fiat currencies more widely.

Trump’s peace deal in the Middle East marks a dialling down in geopolitical tensions. For now, it has stopped the surge in the gold price in its tracks. But the interruption may be only temporary.

In remarks last week, Ken Griffin, the billionaire hedge fund founder of Citadel, said “investors are crowding not only into gold, but also into dollar alternative assets like Bitcoin. It’s hard to believe. It’s really worrisome that people view gold as a haven asset the way they once viewed the dollar.”

Hard to believe, perhaps, but easy to understand. Gold is the world’s oldest, universally accepted currency, with an almost mythical status in the history of money. Rarely have its attributes as a safe haven in troubled times been as much in demand as they are today.

First and foremost, it’s about growing loss of trust in the dollar, and the vast US treasuries market that underpins it. The US may still be a relatively dynamic and fast-growing economy, but it is increasingly sustained by ultimately unaffordable stimulus. Not to mention an AI investment boom that many now think cannot last.

With budget deficits of more than 6 per cent of GDP as far as the eye can see, there’s no sign of a reprieve in the onwards and upwards march of America’s national debt, and seemingly no political appetite for the budget trimming needed to restore sanity to the public finances.

Trump’s attacks on the integrity and independence of the Federal Reserve, his tariff blitz and his rejection of many of the other established norms of economic management have further shaken belief in the dollar as the default currency for international commerce.

‘The Roaring 2020s’

At any one time, financial markets are a mass of conflicting signals and the great irony here is that although international investors are increasingly running scared of US government debt, they cannot get enough of America’s leadership in the innovative industries of AI.

Trump recently claimed that his pro-business, tax cutting and deregulatory agenda had generated new investment commitments of some $17tn (almost £13tn), or more than half the size of US GDP. This is undoubtedly an exaggeration, but there is no quarrelling with the notion of an investment boom of mega proportions.

Here too there are parallels with the “Roaring Twenties” and the subsequent crash. The new industries that investors piled into back then were automobiles, consumer goods, radio, construction and chemicals.

When consumer spending cratered in the subsequent bust, all that investment was left high and dry with nowhere to go. We may be seeing something similar today. Trump’s headlong plunge into financial deregulation further increases the risks. After all, the global financial crisis of 15 years ago was directly connected to the deregulation and “light touch” financial supervision of the preceding decade.

While America burns too hot, Europe is sinking into a quagmire. Britain’s fiscal predicament looks precarious and France’s appears almost terminal. Gripped by political paralysis, there appears to be virtually no chance of the belt-tightening needed to put France back on a firm footing.

For now, our friends across the Channel hide behind the assumed protections of the euro and the German chequebook that underwrites it, but for how much longer can the defences hold? Eventually, without course correction, there will be a moment of all-embracing crisis.

Britain seems equally incapable of the required surgery, despite the apparent advantage of a government with an overwhelming majority and nearly four years to run before it faces re-election.

This ought to provide cover for difficult political choices, but Labour has proved incapable of the spending cuts needed to balance the books or of the measures required to lift the economy out of its low productivity rut.

Cursed by the highest interest rates in the G7, the strains are already evident in mushrooming debt-servicing costs that cut deep into the Government’s ability to fund pressing spending priorities such as defence.

Black October

For financial markets, October is a particularly inauspicious month. Historically, it’s been the autumnal backdrop for some of the worst stock market crashes: the Panic of 1907, the Great Crash of 1929, “Black Monday” in 1987, as well as the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, though this technically began with the collapse of Lehman Brothers the month before.

But crashes can and do happen at any time of year. Predicting precisely when is a mug’s game. Hardly anyone manages it consistently and even when they do get it right, it is more likely to be luck rather than judgment.

So for now, the fear of missing out continues to drive the headlong dash into the artificial intelligence boom. Everyone knows it’s out of control, but as Chuck Prince, the former chief executive of Citigroup, said just ahead of the 2008 financial crisis, “as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance”.

This is the great, intrinsic curiosity of finance – that despite all the lessons of history, it never knows when to stop. Eternally condemned to a cycle of boom and bust, it invariably pushes the envelope of excess until the whole house of cards collapses in on itself.

Triggered

All the stars are now aligned for the mother of all financial meltdowns, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to happen soon. Market collapses require a trigger, or some kind of event that causes the presiding sentiment of greed to turn into panic and fear. We don’t yet see that. Rarely if ever do bull markets simply die of old age.

A case in point is Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the US Federal Reserve. He originally highlighted the dangers of what he famously described as “irrational exuberance” in stock markets as early as 1996, but the dot.com bubble didn’t finally burst until early 2000, some four years later. When markets finally crashed, it was in no small measure Greenspan’s fault.

There had been a mini-crisis in 1998, when a highly-leveraged hedge fund called Long Term Capital Management ran into trouble, threatening a chain reaction of cascading bankruptcies through the financial system. The Fed responded by organising a bailout, cutting interest rates and flooding the system with liquidity, thereby further fuelling the latter stages of the bubble. It was like pouring fuel on the fire.

Something similar could easily occur today. Interest rates are still relatively high by the standards of the post-financial crisis era, leaving plenty of scope for cuts in the event of limited market turbulence. Donald Trump will not want to see a stock market crash and accompanying recession under his watch. The Fed will be under particular pressure to act if and when the storm clouds threaten to burst.

This could keep markets ticking over for some time, but it will only make the final reckoning worse still once gravity eventually reasserts itself. Until then, as they might say on Strictly, we will just “keep dancing”.