There’s still time to save Robert Roberson

Unless something changes, in less than a month, Texas will end Robert’s life despite overwhelming evidence he’s actually innocent.

CLAY JACKSON AND MARGARET AMSHAY

Governor Abbott or the Court of Criminal Appeals can stop this tragedy before it happens. They can prevent Texas from executing an innocent man. The power to stop this injustice lies in their hands, but the pressure must come from ours.

A few months ago, I reached out to the co-author of this essay, Margaret Amshay, to see if she’d be interested in working on a piece about Robert Roberson’s fast-approaching execution date. She said yes within minutes.

I met Margaret last year, just before Robert’s October 2024 execution date, and we quickly bonded over our shared passion for abolishing state murder and seeking justice for Robert.

Margaret is a 2025 graduate of Harvard Law School. She recently passed the bar in North Carolina. Later this fall, she’ll start her career as a public defender with the Mecklenburg County PD’s Office. In law school, she interned for Robert’s post-conviction counsel.

—Clay

A quick word about our shared passion

Clay: My passion for abolishing state murder started my 1L year, in the historic courtroom at Memphis Law—a place that looks like a Grisham novel. The air was filled with the faint smell of too many nervous kids in cheap suits.

The Sixth Circuit was reviewing a habeas petition challenging a death penalty conviction in Thomas v. Westbrooks. The prosecutor representing Tennessee was getting grilled by a skeptical three-judge panel about new information regarding an undisclosed payment to a key state witness.

Judge Gilbert S. Merritt, a lion with a deep commitment to defendants’ constitutional rights, leaned in, voice sharp, eyes steady: “A man’s life is on the line here.”

“A man’s life is on the line here.”

The prosecutor froze, and then, in front of two hundred law students, fainted. Knees buckled. Thud. Everyone gasped. Stress, I’m sure. But also the weight of what was really at stake: A man’s life.

That moment is etched in my memory like stone.

Lawyer and Equal Justice Initiative founder Bryan Stevenson frames the moral question perfectly in his book Just Mercy: it isn’t whether someone deserves to die—it’s whether we deserve to kill.

I’ve carried that line around like a flask of Evan Williams green. It burns, but it also warms.

Margaret: My passion for ending government-sanctioned murder began before law school and it was one of the reasons I applied in the first place. I knew I could not sit idle while injustice unfolded in its most brutal form—the government taking human lives to prove that killing was wrong.

When I arrived at Harvard Law School, I never forgot that conviction. By my 2L year, I joined the Capital Punishment Clinic and was placed in an externship with Sween Law in Austin, Texas. I didn’t know what to expect, but I was welcomed by Gretchen Sween, a brilliant, fearless advocate whose warmth matched her power. That winter, Gretchen took me to death row. There, I met the man whose story has changed my life ever since: Robert Roberson.

I had been nervous to meet Gretchen’s clients. I worried how they might feel about two young interns walking in to speak with them. But the moment I sat across from Robert, those nerves disappeared. He greeted me with kindness, his gentle smile radiating a childlike innocence. The first thing he asked me was my name, my favorite color, and my birthday. When I answered, he smiled and shared his own. From there we talked about simple things like his childhood on a farm, his favorite animals. In that conversation, his faith, his hope, and his simple goodness shone through.

Leaving that prison was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Every public defender knows the sinking feeling—walking out through heavy doors not knowing what you were leaving your clients to endure. Tears welled in my eyes as I left, anger flooding in. How could anyone meet Robert Roberson and still want him dead?

On the way back to Austin, Gretchen explained that when Robert asks about birthdays, he writes them down, remembers them, and always reaches out when they come around. She was right. On June 12, 2024, six months after our first meeting, Robert Roberson was the very first person to wish me a happy birthday. That is who Robert is: a kind, gentle soul whose humanity endures despite the cruelty of the state.

When his execution was stayed last year, I wept with relief. It meant something small but profound—that I would get the chance to wish Robert a happy birthday on November 10, just as he had done for me.

And so I leave you with this simple request: please, allow me to wish my dear friend Robert a happy birthday again this year. It is my greatest wish.

South from Palestine

East Texas is a place where the pine trees hang heavy, the humid summer air tastes like rust and red dirt, and locals don’t talk about the death penalty.

Robert Roberson is from Palestine but has lived most of the last two decades a few hours south inside the infamous death row unit in Livingston, waiting for Texas to decide when and how it will kill him.

A date is set, once again. October 16, 2025.

And unless something changes, unless the courts finally intervene or mercy shows up in a place where mercy is in short supply, Texas will march him down the long green mile and end his life despite overwhelming evidence that Robert is actually innocent.

The alleged crime? The murder of his two-year-old daughter, Nikki, back in 2002. Texas said he shook her to death. Shaken Baby Syndrome was the only explanation. SBS was a slam dunk in American courtrooms for decades. Prosecutors wielded it like gospel; doctors swore to it as if it were scripture. Jurors bought it.

Robert Roberson with his daughter Nikki before she passed away.

Robert Roberson with his daughter Nikki before she passed away.

The problem? SBS is junk science. Discredited. Tweaked and amended—but to date devoid of any evidence-based science to support it. A hollow shell of a theory that has sent folks like Robert to prison for crimes that likely never happened. He is at risk of being the first person ever executed in reliance on this bogus pseudo-science.

The evidence shows Nikki probably died of pneumonia and toxic medications prescribed by doctors who gave her respiratory-suppressing medications to treat a respiratory infection that had caused her fever to spike over 104 degrees. She had countless doctor visits in her 27 short months of life. But the system needed someone to blame.

So it picked Robert—because he was the only person with her when he woke up to find her unconscious and not breathing (something her medical records show happened numerous times before but had never been explained by her doctors).

Palestine in 2003, when Robert’s case went to trial, was not a place where nuance mattered much. The town is God-fearing, pro-law-and-order. Voir dire—the jury selection process—was less about who could weigh evidence fairly and more about who could stomach sentencing Robert to death without flinching.

Prosecutors asked prospective jurors about their views on the death penalty. Those with reservations were shown the door. “Death-qualified” juries are what the system calls them. In practice, they skew heavily toward the execution chamber.

Roberson’s lawyers challenged potential jurors who knew family members, worked at the local hospital, or admitted to having already decided that he “looked guilty.” But Palestine isn’t Austin or Dallas. The jury box swelled with folks who blindly trusted cops and state-aligned doctors, and didn’t need much convincing that a poor, awkward father could snap and shake his daughter to death.

The prosecution’s narrative was clean, simple, and wrong. Nikki had collapsed. She was brought to the hospital unconscious, with some bleeding outside of the brain, brain swelling, and retinal hemorrhages. Those three symptoms were then the holy trinity of SBS. And an explicit SBS diagnosis was made by a doctor after Nikki was transferred to Dallas, where she was removed from life support without her father even being told what was going on.

Doctors turned professional state witnesses lined up to tell the jury that only shaking could’ve caused Nikki’s injuries. No one mentioned pneumonia. No one considered the toxic levels of drugs in her. There had been no investigation of her medical history or recent illness. And Roberson, quiet, socially awkward, emotionally flat, played right into the hands of a grieving community looking for a source of blame. He didn’t act the way a grieving father should.

The defense did not even challenge the State’s SBS theory—despite their client’s steadfast insistence he had not done anything to hurt his daughter. Experts, wrapped in the authority of white coats, all assured the jury that science was on their side.

It didn’t take long. Guilty. Death.

What they didn’t hear? That SBS had no scientific foundation; that new research was already calling it into question; that evidence-based science would eventually refute all of its premises that had been simply accepted as gospel.

What they didn’t see? That Nikki’s medical records showed repeated doctor and hospital visits, undiagnosed pneumonia, and prescribed drugs now considered unsafe for children.

What they didn’t know? That time would prove SBS dead wrong. That two decades later, countless SBS convictions would be overturned across the country.

Robert’s been at the Polunsky Unit in Livingston ever since, watching the seasons change from behind bars.

In 2016, his execution was stayed when his lawyers argued SBS was junk science. Texas had recently passed Article 11.073—its Junk Science Law—allowing certain convictions to be revisited when the science collapses under its own weight. For a moment, there was hope.

But the machinery of death doesn’t stop easily. Especially in Texas. Appeals wound through courts, petitions denied, evidence dismissed without examining the merits. Prosecutors doubled down, unwilling to admit they’d built a death sentence on sand.

“The wrongful conviction of Robert Roberson has been an ongoing tragedy for over 20 years.” —John Grisham

A miracle just before midnight

Fast forward to the summer of 2024. Robert’s execution was set for October 17th. What followed was nothing less than a desperate, brutal fight for his life.

The media smelled the story. Headlines blared, cameras rolled, and outlets across the country dissected the case. But while the public began to stir, the real question remained: were the people who mattered, the ones with the power to stop the killing, paying attention? Were they listening?

Robert’s attorney threw every legal Hail Mary possible, filing motion after motion, plea after plea. Each one was swatted down. Every denial landed like a gut punch, leaving less air in the room, less time on the clock.

Then came the wait for the parole board’s recommendation. Would they recommend mercy? Would Abbott break his silence?

Mercy proved scarce. The board turned its back, unanimously voting against clemency—without any hearing, without any explanation. The writing on the wall grew darker: Abbott wouldn’t save Robert. And with that, the path narrowed to almost nothing.

Hope was evaporating. Every door slammed shut. Every route to justice collapsed into dust.

And then, something completely unexpected happened.

Robert’s case broke through the political noise. A bipartisan group of Texas lawmakers decided they couldn’t simply stand by. Last September, they drove to Livingston to meet Robert face-to-face. Inside the prison chapel, unshackled, Robert greeted them. That the Texas Department of Criminal Justice allowed this rare opportunity is itself a testament to the simple truth: the folks who work beside Robert every day know he is not a threat.

The lawmakers spoke with Robert, prayed with him, and listened as he shared his hopes and dreams. And when they walked away, they carried with them the same realization that so many others have after meeting him: Robert is an inspiration.

“I thought I’d be bringing Robert a message of hope today, but instead, I left inspired myself,” said State Representative Joe Moody.

“He’s clearly suffered greatly, but he was still optimistic and future focused as he told us about the good he wants to do for other people who’ve gone through what he’s experienced. His faith and spirit just reinforced my commitment to fighting for him so that he has that chance—and so that this injustice never happens to another Texan.”

Moody and his colleagues didn’t let the fight end at the prison gates. They carried that conviction with them, into the press, into the chambers of power, into the final hours of Robert’s life. And it was in those final moments, with time all but gone, that they took the step that would quite literally save him—for a year, at least.

In the days leading up to last October’s death date, time became its own torment, each minute dragging like a century, yet vanishing in an instant. Supporters flooded Abbott’s office with desperate calls, begging for mercy. Still, the clock pressed on, ruthless and unrelenting. Abbott and Paxton’s silence was deafening.

Then, on the eve of his execution, lawmakers took a step that shattered precedent. In an extraordinary move, the Texas House Committee on Criminal Jurisprudence subpoenaed Robert to testify about Texas’s junk science law. The date set for his testimony was October 21st, 4 days after he was scheduled to die. You can’t subpoena a dead man.

With that act, they forced a constitutional showdown. Would Robert live to testify before the committee, or would Texas kill him in defiance of its own legislature? As October 17th dawned, the answer remained agonizingly unclear. The hours slipped away. By nightfall, Robert, a likely innocent man, sat in Livingston where he had been moved to the execution chamber, staring down death, as the clock marched toward midnight.

Less than two hours before the execution warrant would have expired, a glimmer of hope broke through.

The Committee secured a temporary restraining order blocking Texas from moving forward. Relief surged, only to be crushed moments later when the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals stayed the injunction. The machine of death roared back to life.

And yet, the lawmakers refused to surrender. In a last-second, desperate bid, they turned to Abbott’s former colleagues on the Texas Supreme Court. The clock was nearly out. Inside the execution chamber, Robert prayed and prepared to die. Then, late into the 11th hour, Texas’s high court granted a temporary stay. The execution was halted. Robert’s life was spared, at least for the moment.

When he learned the news, Robert praised God and thanked his supporters. Against all odds, hope had pierced the darkness. The faith that Robert clung to down to the last second had proven stronger than the machinery of death, and once again, he reminded us all what it means to believe when belief seems impossible.

The clock starts again

After the fleeting joy of Robert’s survival, the questions began. What now? At midnight on October 17, the death warrant expired, sparing Robert’s life. By Texas law, no new date could be set for at least 90 days. For the first time in a while, Robert had a window of safety. But what would happen in the next three months? Would he finally get the chance to testify on October 21st and tell his story?

The answer, of course, was no. Paxton’s office jumped in and fought relentlessly to keep the public from hearing from Robert while making numerous misrepresentations about Robert and the case. The truth was politically inconvenient. After more than two decades on death row, Robert finally had the chance to tell the world of his innocence. Instead, state officials blocked him from testifying, citing “safety concerns.”

The irony was almost unbearable. This was from the same state that allowed Robert to meet unshackled with lawmakers in the prison chapel. Anyone who has met Robert knows his gentle, kind nature. Safety was never the issue; silencing him was.

His advocates pushed back, reminding lawmakers that Robert’s autism would make virtual testimony a cruel substitute. Still, Texas’s cruelty prevailed. Robert was gagged. But the voices of others could not be silenced.

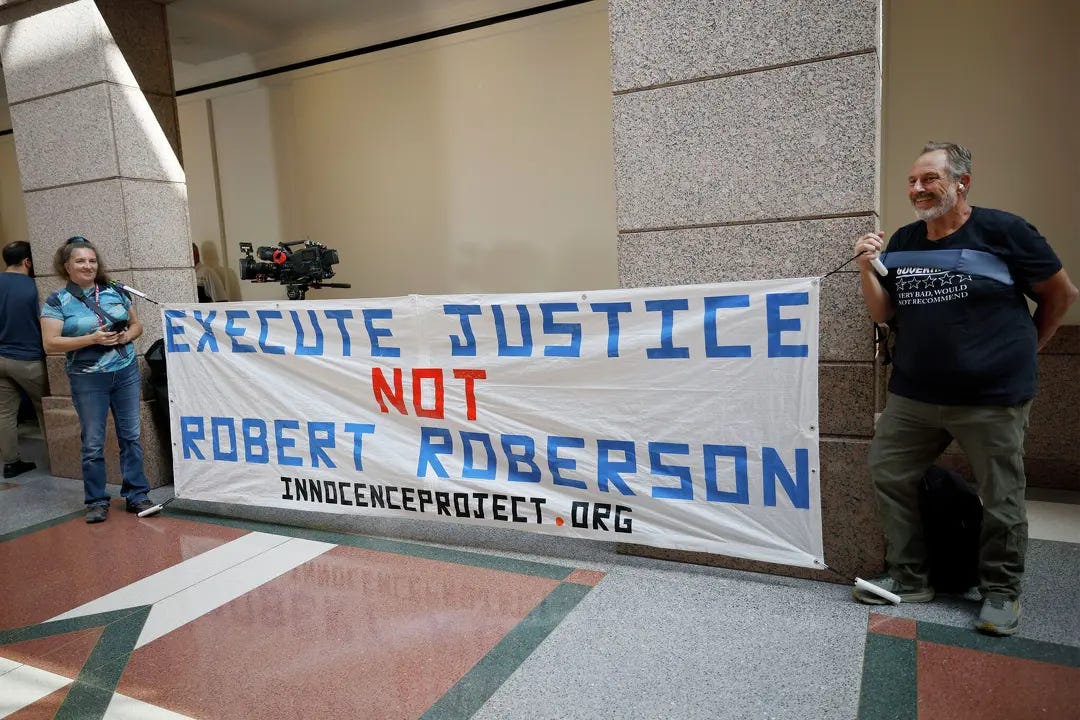

On October 21st, the Committee pressed forward, hearing hours of testimony from those who knew Robert’s case best—advocates including John Grisham, Dr. Phil, medical experts, the lead detective from Robert’s own prosecution, and even a juror from Robert’s trial. Each one brought evidence of a grave injustice. Each one shared the same conviction: Robert Roberson is innocent.

The most stunning moment came when Terre Compton, one of the twelve jurors who convicted Robert, testified. She explained the jury’s decision hinged entirely on what Texas told them about SBS. Then came the exchange that left the room frozen:

Rep. Brian Harrison: “Did the jury hear everything you needed to hear to make a correct decision?”

Compton: “No.”

Harrison: “Knowing what you know now, do you believe Robert Roberson murdered his daughter?”

Compton: “No.”

Harrison: “How strongly do you feel about that?”

Compton: “100%.”

That one hundred percent thundered through the room. One of the twelve people who condemned Robert to death now said without hesitation that he was innocent.

Later, Compton told CNN: “I don’t think it really hit me so hard until they set his death date. We as jurors took what they told us to be the truth. … I feel like we were taken very much advantage of. I think they lied to us in a lot of ways.”

The truth was powerful—and dangerous. Political operatives wasted no time striking back. Paxton’s office released misleading statements, painting Robert as a monster, desperate to drown out the voices rising in his defense. The message was clear: this fight was far from over.

For months, Robert’s advocates battled to secure his testimony. But when the new legislative session began, the committee dissolved. The legislature would no longer be in a position to step in and save him.

Then, silence. No new execution date was set. For a brief moment, it seemed the machinery of death had moved on. But Robert wasn’t so lucky.

Despite a new habeas application filed this February supported by powerful evidence of his innocence—evidence no court has ever considered—Texas pressed forward. In June, Paxton’s office took control of the case from the Anderson County District Attorney and immediately pushed for a new death date. A Smith County judge signed the order.

Robert Roberson is once again scheduled to die. On October 16th. Exactly 364 days since he last sat mere feet from the execution chamber.

The clock started ticking again.

While the clock ticks toward October 16, the fight to save Robert is far from over. New revelations have upended what Robert and his attorneys thought they knew about the removal of Nikki from life support and the hearings that followed. Hearings that quickly led to the stripping of Robert’s parental rights and the start of the capital case. These discoveries reveal evidence of judicial misconduct that further stains the case and magnifies the cruelty of his story.

This crucial information came to light through a third party. After Robert’s latest execution date was set, Republican Texas House Representative Lacey Morgan Hull contacted his attorney with a chilling discovery. In February, during a meeting with representatives from Children’s Medical Center of Dallas (CMCD), Representative Hull learned that before Nikki was taken off life support, CMCD had followed internal protocols. She was told that the hospital had verified Nikki’s legal conservatorship by contacting the court in Anderson County and had been informed that Nikki’s maternal grandparents were the legal guardians with authority to make end-of-life decisions affecting her.

But this information CMCD received from the Anderson County Judiciary was false. The Bowmans had no such authority; Robert was Nikki’s sole legal conservator. Under Texas law, only he had the power to make decisions regarding life-sustaining care.

According to Representative Hull’s affidavit, this was “the first time” that CMCD became aware that it “had been misinformed by Anderson County about who had authority to withdraw life-sustaining treatment from Mr. Roberson’s daughter Nikki when that action was taken.”

For years, it was assumed that the Bowmans alone had misrepresented their authority. But new revelations make it clear the judiciary itself played a role. A judiciary who had access to the custody records, and who knew Robert had legal custody, provided false information that enabled Nikki’s removal from life support, paving the way for Robert’s arrest. As Robert’s attorney now argues, this was no mere oversight. It was at least reckless, and it violated both his parental and constitutional rights.

What followed only compounds the injustice. Nikki was pronounced dead on February 1, 2002. That same night, before an autopsy could be performed, an Anderson County judge signed a warrant charging Robert with capital murder—based entirely on a since-discredited Shaken Baby Syndrome diagnosis. Three days later, the Bowmans filed a motion to strip Robert of custody and claim the right to bury his daughter. Judge Jerry Calhoon, without providing Robert notice or hearing, granted the motion.

Judge Calhoon should have recused himself from Robert’s case. His son, Mark Calhoon, was the prosecutor leading the capital murder charge. Yet Judge Calhoon inserted himself, not only terminating Robert’s parental rights but also taking the extraordinary step of appointing his criminal defense lawyer. That lawyer, Steve Evans, had some ties to the local hospital—the same hospital that treated Nikki repeatedly, including twice during the last week of her life. The same hospital that missed Nikki’s pneumonia in the days leading up to her death.

Robert himself knew he was being railroaded. In notes seized from his jail cell before trial, his desperation poured out:

“My attorneys are not representing me professional!”

“Lawyers [are] misrepresenting me.”

“[They] Falsely accusing me of things that I haven’t done. So what’s the deal anyway? You both need to get off your butts and represent me fairly. I thought that you both suppose to be working for me? So what’s the problem anyways? I think I’m getting railroaded by you all getting me to say that I done something when I haven’t done a damn a thing.”

Robert’s attorney never pursued his innocence claim. Instead, Steve Evans stood before the jury and conceded it was a shaken baby case, despite Robert never once wavering in his claim that he had done nothing wrong.

From the very beginning, Robert was trapped in a system stacked against him—a system that violated his rights as a father, corrupted his trial with conflicts of interest, and silenced the truth. This new evidence of judicial misconduct confirms it: his fundamental rights were violated from the outset.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals cannot ignore this. They must grant Robert Roberson a stay and a new trial. If they do not, the State of Texas will not just kill an innocent man, it will kill the last shred of faith that justice exists at all.

You want to see tyranny? Just watch an execution.

Livingston’s death house isn’t cinematic. It’s banal. A squat brick building that could pass for a DMV if not for the barbed wire. Inside, time stands still.

Here’s how it will go, unless some authority intervenes:

At dawn, Roberson will be moved to a holding cell a few feet from the death chamber. He’ll be offered his last meal—not the mythical smorgasbord of movies, but something cooked in the prison kitchen. Burgers, fried chicken, a milkshake if the machine’s working.

The warden will check in. Chaplains will circle. Guards will walk him down the hallway, a slow shuffle down the plank. He’ll be strapped to the gurney—arms out, leather restraints across chest and legs.

Witnesses will file in. On one side of the glass, Nikki’s maternal relatives, if they choose to come. On the other, Nikki’s paternal relatives and other supporters of Robert’s humanity. Reporters in the back row, notebooks open, waiting to record the moment death becomes official.

The needle will slide drugs, acquired under the cloak of secrecy, into his veins. It will burn. His chest may heave. The witnesses will watch as his body goes still. A doctor will declare him dead.

The whole thing will take twenty minutes. Less, if he’s lucky.

And then the curtain will close.

But this end is preventable.

If Governor Abbott or the Court of Criminal Appeals act, they can stop this tragedy before it happens. By granting Robert Roberson a stay, they can prevent Texas from executing an innocent man—a stain of injustice that can never be erased. The power to stop this injustice lies in their hands, but the pressure must come from ours.

Forever haunted

The strange thing about Robert’s case is that even the people who built it don’t believe it anymore. Brian Wharton, the former chief detective in Palestine, has said flat out:

“I will forever be haunted by my participation in his prosecution. I am firmly convinced Robert is an innocent man.”

That alone should stop the machinery cold, right? When the head cop who put you away begs for your life, shouldn’t that matter? In Texas, it barely registers. Finality is the state’s favorite word.

The finality freaks will say Roberson already had his trial. He already had his appeals. He lost. Time’s up. They’ll talk about finality like it’s some sacred cow.

But what’s finality worth if the underlying science was garbage? If the testimony was wrong? If he was saddled with appointed lawyers for years who disregarded his claim of innocence and did not investigate? If all of the new evidence finally unearthed is simply ignored? If an innocent man will die?

This is where the conservative legal movement stumbles.

Unless those in power have the courage, like former detective Brian Wharton, to admit that grave mistakes were made, the doors stay shut. And in October, that means death for a man who is likely innocent.

Mark it down. Unless something changes, Robert Roberson will be strapped to a gurney this October. They’ll push a needle into his arm, pump poison into his veins, and declare justice served. The press will write a paragraph or two. The state will close the books.

But the story will linger. The detective who regrets it. The lawyers who begged for justice. The family who lost a beloved child and then her father. The rest of us, who looked away.

As Bryan Stevenson would say, the real question isn’t whether Robert Roberson deserves to die for being an autistic father unable to explain his daughter’s complex medical condition and make his distress understood. The real question is whether we deserve to kill him.

We don’t.