“Go Talk To Bill Gates About Me”: How JP Morgan Enabled Jeffrey Epstein’s Crimes, Snagged Netanyahu Meeting

ZeroHedge.com

On an autumn day in 2011, Jeffrey Epstein stepped into JPMorgan Chase’s headquarters at 270 Park Avenue and rode the elevator to the executive floors where the bank’s leaders, including Chief Executive Jamie Dimon, kept their offices. Epstein, who had pleaded guilty to a sex crime in Florida three years earlier, had a message for the bank’s top lawyer, Stephen Cutler: he had “turned over a new leaf,” he said, and powerful friends could vouch for him. “Go talk to Bill Gates about me.”

Key takeaways:

- Epstein was connected to Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu, not just former PM Ehud Barak

- He wired ‘hundreds of millions of dollars in payments to Russian banks and young Eastern European women‘

- Accounts for young women were opened without in-person verification (in one case a SSN could not be confirmed)

- Jes Staley was constantly running interference for Epstein vs. JPM compliance concerns

- At Jes Staley’s urging, compliance spoke with Epstein’s lawyer Ken Starr, who insisted “no crimes” had been committed.

- Epstein had accounts at JPM for at least 134 (!) entities

- JPMorgan funded/serviced pieces tied to Ghislaine Maxwell (millions, incl. $7.4M for a Sikorsky helicopter) and helped finance MC2, the modeling agency linked to Jean-Luc Brunel.

For more than a decade, JPMorgan Chase processed over $1 billion in transactions for Jeffrey Epstein – including hundreds of millions routed to Russian banks and payments to young Eastern European women, opened at least 134 accounts tied to him and his associates, and even helped move millions to Ghislaine Maxwell – including $7.4 million for a Sikorsky helicopter – while anti–money laundering staff repeatedly flagged large cash withdrawals and wire patterns aligned with known trafficking indicators, according to a new report from the NY Times following a six-year investigation that involved “some 13,000 pages” of legal and financial records. Funny how they sat on this until now – maybe it’s related to this, but do read on.

Inside JPMorgan, the debate over whether to keep Epstein as a client had been simmering for years. Epstein was lucrative. His accounts held more than $200 million and generated millions in fees, and he opened doors to wealthy prospects and world leaders. He had helped midwife the bank’s 2004 purchase of Highbridge Capital Management, earning a $15 million payday. Senior bankers credited him with introductions to figures such as Sergey Brin and Benjamin Netanyahu.

Sure enough, just as more bank employees were losing patience with Epstein in 2011, he began dangling more goodies. That March, to the pleasant surprise of JPMorgan’s investment bankers in Israel, they were granted an audience with Netanyahu. The bankers informed Staley, who forwarded their email to Epstein with a one-word message: “Thanks.” (The bank spokesman said JPMorgan “neither needed nor sought Epstein’s help for meetings with any government leaders.”) And around that same time, Epstein presented an opportunity that, like the Highbridge deal years earlier, had the potential to be transformative.

This one involved Bill Gates, who had only recently entered Epstein’s orbit. In an apparent effort to ingratiate — and further entangle — himself with his bankers and the Microsoft co-founder, Epstein pitched Erdoes and Staley on creating an enormous investment and charitable fund with something like $100 billion in assets. -NY Times

Compliance leaders urged the bank to “exit” the felon after anti–money laundering personnel flagged a yearslong pattern of large cash withdrawals and constant wires that, in hindsight, matched known indicators of trafficking and other illicit conduct.; instead, top executives overrode objections at least four times, allowed accounts for young women to be opened with scant verification, and paid Epstein directly – the aforementioned $15 million tied to a hedge-fund deal and $9 million in a settlement. Even in 2011, as concerns mounted, internal notes referenced decisions “pending Dimon review,” while Jes Staley, a senior executive and Epstein confidant, traded sexually suggestive messages (“Say hi to Snow White”) and shared confidential bank information with the client.

Exact dollar figures and destinations across years:

- $1.7M in cash (2004–05) and earlier $175K cash (2003).

- $7.4M wired to buy Maxwell’s Sikorsky helicopter.

- $50M credit line approved in 2010 even post-plea; ~$212M then at the bank (about half his net worth).

- $176M moved to Deutsche Bank after the 2013 exit.

JPM of course regrets everything – calling their relationship with Epstein “a mistake and in hindsight we regret it, but we did not help him commit his heinous crimes,” Joseph Evangelisti, a JPMorgan spokesman, said in a statement. “We would never have continued to do business with him if we believed he was engaged in an ongoing sex trafficking operation.” The bank has placed much of the blame on Jes Staley, then a rising executive and close confidant of Epstein. “We now know that trust was misplaced,” Evangelisti said.

A Client Too Valuable To Lose

Epstein’s ties to JPMorgan reached back to the late 1990s, when then–Chief Executive Sandy Warner met him at 60 Wall Street and urged a lieutenant, Mr. Staley, to do the same. Epstein soon became one of the private bank’s top revenue generators. A 2003 internal report estimated his net worth at $300 million and attributed more than $8 million in fees to him that year.

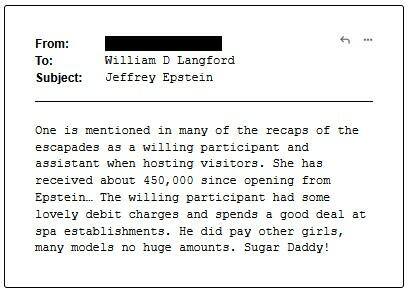

Even then, there were warning signs. In 2003 alone, he withdrew more than $175,000 in cash. Bank employees recognized the need to report large cash transactions to federal monitors but failed to treat the withdrawals as a signal of deeper risk. In the years that followed, compliance staff repeatedly expressed alarm over Epstein’s wires, cash activity and requests to open accounts for young women with minimal verification. One internal note, describing large transfers to an 18-year-old totaling “about 450,000 since opening,” read: “Sugar Daddy!”

Still, influence carried weight. Epstein was prized not only for his personal balances but for the business he brought in. Through his network, which included hedge fund founder Glenn Dubin and a constellation of billionaires and officials, he introduced potential clients and helped shape the bank’s strategy. The Highbridge deal was heralded internally as “probably the most important transaction” of Mr. Staley’s career.

Internal Dissent, Repeatedly Overruled

From 2005 to 2011, the bank’s leaders revisited the Epstein question several times. In 2006, after a Florida indictment alleging solicitation from a teenage girl, JPMorgan convened a team to decide whether to exit the client. The bank swiftly jettisoned another customer, the actor Wesley Snipes, when he faced tax charges. It did not do the same with Epstein. Instead, it imposed a narrow restriction – not to “proactively solicit” new investments from him – while continuing to lend and move his money.

Within the bank, even casual exchanges betrayed an awareness of Epstein’s proclivities. “So painful to read,” Mary Erdoes, now head of asset and wealth management, emailed upon seeing news of the indictment. Mr. Staley replied that he had met Epstein the prior evening and that Epstein “adamantly denies” involvement with minors. At other moments, the tone turned flippant. Describing a Hamptons fundraiser, Mr. Staley wrote that the age gaps among couples “would have fit in well with Jeffrey,” to which Ms. Erdoes replied that people were “laughing about Jeffrey.”

By 2008, after Epstein pleaded guilty and registered as a sex offender, pressure mounted to end the relationship. “No one wants him,” one banker wrote. Mr. Cutler, the general counsel, would later say he viewed Epstein as a reputational threat – “This is not an honorable person in any way. He should not be a client.” Yet he did not insist on expulsion, and the matter was not escalated to Mr. Dimon. Epstein remained.

In early 2011, William Langford, head of compliance and a former Treasury official, urged that Epstein be “exited.” He warned that ultrawealthy clients could warp judgment and that patterns in Epstein’s accounts resembled those of trafficking networks.

The bank’s head of compliance, William Langford, was especially alarmed. “No patience for this,” he emailed a colleague. Langford had joined JPMorgan in 2006 after years of policing financial crimes for the Treasury Department. He knew — and had warned colleagues — that companies can be criminally charged for money laundering if they willfully ignored such activities by their clients. He saw ultrawealthy customers as a particular blind spot; all the time that private bankers spent wining and dining these lucrative clients could cloud judgments about their trustworthiness. It looked like that was what was happening with Epstein. One of Langford’s achievements at JPMorgan was the creation of a task force devoted to combating human trafficking. The group noted in a presentation that frequent large cash withdrawals and wire transfers — exactly what employees were seeing in Epstein’s accounts — were totems of such illicit activity.

…

Langford said in a deposition that he started off by quickly explaining the human-trafficking initiative. In that context, how could the bank justify working with someone who had pleaded guilty to a sex crime and was now under investigation for sex trafficking? -NY Times

Mr. Staley pushed back, relaying Epstein’s insistence that allegations would be overturned. Days later, the bank agreed to keep the accounts open.

Money, Access and a Second Chance

Even as internal skepticism grew, Epstein stayed in touch with his former private banker, Justin Nelson, and continued to surface in meetings involving Leon Black, a billionaire client. Staley remained close to Epstein for years, exchanging personal messages and visiting his residences, even as he ascended to run Barclays. In 2019, after Epstein was arrested on federal sex trafficking charges and later died by suicide in a Manhattan jail, investigators, journalists and regulators turned anew to his banking relationships.

JPMorgan launched an internal review, code-named Project Jeep, and filed belated suspicious activity reports flagging about 4,700 Epstein transactions totaling more than $1.1 billion. The bank settled civil claims with Epstein’s victims for $290 million and with the U.S. Virgin Islands for $75 million, without admitting wrongdoing. No executives lost their jobs. Mr. Dimon, who testified that he did not recall knowing about Epstein before 2019, remains one of the most powerful figures in American finance.

To Bridgette Carr, a law professor and anti-trafficking expert retained by the Virgin Islands, the case poses a larger question about incentives. JPMorgan, she concluded, enabled Epstein’s crimes. “I am deeply worried here that the ultimate message to other financial institutions is that they can keep serving traffickers,” she said. “It’s still profitable to do that, given the lack of substantial consequences.”